Visual acuity enhancement

Visual acuity enhancement is defined as a heightening of the clearness and clarity of vision. This results in the visual details of the external environment becoming sharpened to the point where the edges of objects become perceived as extremely focused, clear, and defined. The experience of this acuity enhancement can be likened to bringing a camera or projector lens that was slightly blurry into focus. At its highest level, a person may experience the ability to observe and comprehend their entire visual field simultaneously, including their peripheral vision. This is in contrast to the default sober state where a person is only able to perceive the small area of central vision in detail.[1]

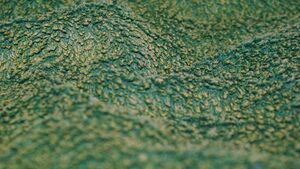

While under the influence of this effect, it is common for people to suddenly notice patterns and details in the environment they may have never previously noticed or appreciated. For example, the complexity and perceived beauty of the visual input often become apparent when looking at sceneries, nature, and everyday textures.

Visual acuity enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as color enhancement and pattern recognition enhancement.[2][3] It is most commonly induced under the influence of mild dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of certain stimulants and dissociatives such as MDMA or 3-MeO-PCP.

Image examples

| Caption | |

|---|---|

| Tree Bark by Chelsea Morgan |

| Towel by Chelsea Morgan |

| Moss on tree Bark by Chelsea Morgan |

Analysis

It is thought that a fundamental feature of information-processing dysfunction in both hallucinogen-induced states and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders is the inability of these people to screen out, inhibit, filter, or gate irrelevant stimuli and to attend selectively to more important features of the environment.[4][5][6]

The CSTC model of the brain posits that the thalamus plays a key role in controlling or gating external sensory information to the conscious faculties and is thereby fundamentally involved in the regulation of a person's awareness and attention.[7][8][9][10] The interruption of psychedelics to these neural pathways that inhibit the sensory gating systems[10][11] may, therefore, result in an enhanced availability of sensory information which is usually filtered out by these systems. This process is likely also involved in the various visual, tactile, and auditory enhancements which commonly occur when under the influence of a psychedelic experience.

It is important to note that while environmental gating may be lowered, psychedelics' suggestibility intensifications and restructuring of internalized hierarchy of narratives within conscious experience plays a role in projecting personal biases outwards in the form of hallucinations. A psychedelic experience is not by necessity a 'more raw' version of reality.

Psychoactive substances

Compounds within our psychoactive substance index which may cause this effect include:

- 1B-LSD

- 1P-ETH-LAD

- 1P-LSD

- 1V-LSD

- 1cP-AL-LAD

- 1cP-LSD

- 1cP-MiPLA

- 2-Aminoindane

- 25B-NBOH

- 25B-NBOMe

- 25C-NBOH

- 25C-NBOMe

- 25D-NBOMe

- 25E-NBOH

- 25I-NBOH

- 25I-NBOMe

- 25N-NBOMe

- 2C-B

- 2C-B-FLY

- 2C-C

- 2C-D

- 2C-E

- 2C-I

- 2C-P

- 2C-T

- 2C-T-2

- 2C-T-21

- 2C-T-7

- 3,4-CTMP

- 3-MeO-PCE

- 3-MeO-PCP

- 3C-E

- 3C-P

- 4-AcO-DET

- 4-AcO-DMT

- 4-AcO-DiPT

- 4-AcO-MET

- 4-AcO-MiPT

- 4-HO-DET

- 4-HO-DPT

- 4-HO-DiPT

- 4-HO-EPT

- 4-HO-MET

- 4-HO-MPT

- 4-HO-MiPT

- 5-MAPB

- 5-MeO-DALT

- 5-MeO-DMT

- 5-MeO-DiBF

- 5-MeO-DiPT

Experience reports

Anecdotal reports which describe this effect within our experience index include:

- Experience: 1.5g Psilocybe Cubensis - Analysis of body and mind

- Experience: 15mg 2C-B (oral) - A pleasant low-dose evening with Nexus

- Experience: 36mg 4-AcO-DiPT - Truly, one for the psychedelic animals among us

- Experience: 5-EAPB (60mg) + 2-FMA (20mg) + 4-AcO-DMT (10mg) - Emotional catharsis

- Experience:150mg MDMA + 20mg 2C-B - I designed it this way myself

- Experience:2.5g Mushrooms + 500mg DMT

- Experience:20mg - I looked up and saw an angry god-like figure made of clouds glaring down at me

- Experience:25mg 3-MeO-PCP - Enhanced film experience

- Experience:26mg - Stage 3 Trip

- Experience:2mg 25C-NBOMe - Experimental trip to test personal limits of NBOMes

- Experience:3 Grams of Mushrooms - Reset on my Life, Experiencing Satori and the Cosmic Perspective

- Experience:3 drops of cinnamon bark oil/ 5 drops of german chamomile oil/ 2mL of nutmeg oil in lecithin - experiments with nutmeg oil

- Experience:3.5g psilocybe cubensis - Relinquishing of Material Chains/Fear and Desolation

- Experience:300µg LSD - Togetherness and the Silent Dusk

- Experience:337mg DMT fumarate - A Day With DMT

- Experience:3g mimosa / 3g syrian rue - Connecting with my body

- Experience:4.5g - The Grand Introduction to Beauty and Fear

- Experience:40mg - Brothermind and the Forest's Hand

- Experience:4x 200ug tabs - You do not need to understand

- Experience:5.3g psilocybe cubensis - Dimensional Circumstance and the Fabric of Understanding

- Experience:60mg 4-AcO-DMT Nonstop Quasi-Orgasmic Objectless Euphoria

- Experience:800 seeds LSA - My First Trip Ever

- Experience:BK-2C-B - Various experiences

- Experience:LSA (20 HWBR seeds) – A pleasant adventure with a harsh body load

- Experience:LSD (120ug) - An Overdose of LSD and Trip into Insanity

- Experience:Mushrooms (~0.5 g) - Autonomous Voice

- Experience:Mushrooms and Snuff Films -- Trip Report (3.5 grams)

- Experience:Psilocybin Mushroom (0.16 g, Oral) - Dosage Independent Intensity

See also

External links

References

- ↑ Sardegna, J., Shelly, S. (2002). The Encyclopedia of Blindness and Vision Impairment. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9780816066230.

- ↑ Papoutsis, Ioannis; Nikolaou, Panagiota; Stefanidou, Maria; Spiliopoulou, Chara; Athanaselis, Sotiris (2014). "25B-NBOMe and its precursor 2C-B: modern trends and hidden dangers". Forensic Toxicology. 33 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s11419-014-0242-9. ISSN 1860-8965.

- ↑ Bersani, Francesco Saverio; Corazza, Ornella; Albano, Gabriella; Valeriani, Giuseppe; Santacroce, Rita; Bolzan Mariotti Posocco, Flaminia; Cinosi, Eduardo; Simonato, Pierluigi; Martinotti, Giovanni; Bersani, Giuseppe; Schifano, Fabrizio (2014). "25C-NBOMe: Preliminary Data on Pharmacology, Psychoactive Effects, and Toxicity of a New Potent and Dangerous Hallucinogenic Drug". BioMed Research International. 2014: 1–6. doi:10.1155/2014/734749. ISSN 2314-6133.

- ↑ "Preliminary evidence of an association between sensorimotor gating and distractibility in psychosis". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 8 (1): 60–66. 1996. doi:10.1176/jnp.8.1.60. ISSN 0895-0172.

- ↑ McGhie, Andrew; Chapman, James (1961). "Disorders of attention and perception in early schizophrenia". British Journal of Medical Psychology. 34 (2): 103–116. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1961.tb00936.x. ISSN 0007-1129.

- ↑ Vollenweider, F. (2007). "Advances and Pathophysiological Models of Hallucinogenic Drug Actions in Humans: A Preamble to Schizophrenia Research". Pharmacopsychiatry. 31 (S 2): 92–103. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979353. ISSN 0176-3679.

- ↑ Goddard, A. W., Charney, D. S. (1997). "Toward an integrated neurobiology of panic disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 Suppl 2: 4–11; discussion 11–12. ISSN 0160-6689.

- ↑ Steriade, M (1988). "Intrathalamic and brainstem-thalamic networks involved in resting and alert states". Cellular Thalamic Mechanisms.

- ↑ Steriade, M; McCormick, D.; Sejnowski, T. (1993). "Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain". Science. 262 (5134): 679–685. doi:10.1126/science.8235588. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Vollenweider, Franz X; Geyer, Mark A (2001). "A systems model of altered consciousness: integrating natural and drug-induced psychoses". Brain Research Bulletin. 56 (5): 495–507. doi:10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00646-3. ISSN 0361-9230.

- ↑ Vollenweider, Franz X (1998). "Recent advances and concepts in the search for biological correlates of hallucinogen-induced altered states of consciousness". Heffter Review of Psychedelic Research. 1: 21–32.